This is not the cutting edge. It is the abrasive, jagged edge of history, culture, and society.

Friday, December 31, 2021

Thursday, December 30, 2021

NZ Journalist Becomes First Person With Māori Face Tattoo to Present Primetime News

Wednesday, December 29, 2021

E.O. Wilson, famed entomologist and pioneer in the field of sociobiology, dies at 92

Pioneering biologist, environmental activist and Pulitzer Prize-winning author Edward O. Wilson has died. He was 92.

The influential and sometimes controversial Harvard professor first made his name studying ants — he was often known as "the ant man." But he later broadened his scope to the intersection between human behavior and genetics, creating the field of sociobiology in the process. He died on Sunday in Burlington, Mass., the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation said in an announcement on its website.

Desmond Tutu: South Africa anti-apartheid hero dies aged 90

Saturday, December 25, 2021

Joan Didion obituary

Tuesday, December 21, 2021

Book Review

In ancient Rome, Somnus (otherwise known as Hypnos in Greece) was a personification of sleep. He lived in a cave that contained the river Lethe(forgetfulness). Somnus is only tangentially connected to Cicero via and time and place but he is being mentioned here because he visited me several times while I was reading Cicero’s Selected Works. Without diminishing its historical importance, I will say that this book was a crashing bore that persistently made me drowsy and Somnus successfully lured me into his cave several times throughout the course of this short 200 page essay collection.

Cicero was a Roman statesman, neither patrician nor plebeian and also an outsider because of his obsessive-compulsive insistence on moral purity and honesty at any cost. He came from the Stoic school of philosophers. It could be tempting to say that Cicero’s political life was more exciting than his ideas, he had five men executed in the Catilinian Conspiracy to prevent the senate from being overthrown and he supported the assassination of Julius Caeser, but he is most famous for his oratorical skills and writings in Latin concerning the ethical branch of philosophy.

Since Cicero’s forte was public speaking, this collection opens with a transcribed speech in which he denounces Verres, the corrupt governor of Sicily. He denounces Verres for nepotism, bribery, and debauchery while declaring the superiority of running government as a system of laws as opposed to the tyranny of men. As far as speeches go, this is a good one with precise phrasing, effective punctuation, rhythmic cadences, a mixture of abstract and concrete ideas , and a sufficient buildup of thematic tensions to keep the audience engaged. Compare this to the transcribed speeches of Martin Luther King Jr. or Barack Obama and you can see how a good speech works just as well in writing as it does in speaking. Hearing it spoken in the echoing chamber of the Roman senate must have been impressive. But a clear picture of Cicero, with his Apollonian self-righteousness, begins to emerge early on. While I am inclined to agree with Cicero that honesty in government is necessary, if I wanted to have a good time, I would rather seek out the company of Verres.

The essay “The Second Phillippic Against Antony” is another work of character assassination that targets another individual. Again, despite the moral indignation, Cicero makes Antony look like an interesting character in contrast to Ciecro’s high ground which certainly is higher but certainly not exciting. Antony, after all, was the guy who got to fuck Cleopatra. In these polemics, Cicero presents us with such a stark contrast of the rigid orderliness of Apollonian ethics and the disorienting, life affirming celebrations of Dionysus, the polar tensions that have defined the human experience up until the present day.

The second section of Selected Works is a collection of excerpts from letters Cicero wrote to his friends and colleagues, many of which were penned during his time of exile from Rome. He comments on politics and some battles. There isn’t anything of interest here unless you are deeply immersed in the study of Roman history. These read like footnotes and supplements to a more significant work on the history of the empire and as a casual reader, I didn’t get much out of them.

Moving on, there is a dull essay called “on Duties” pertaining to ethics and honesty, mostly in regards to commerce and the marketplace. No doubt, this Stoic philosopher probably had his own personal grievance in this matter since when he returned from exile, he found that his property had been confiscated and sold without his permission, although I am not sure if that happened before or after this essay was written. I actually don’t care enough to bother checking the dates. Cicero uses the criteria of moral righteousness and advantage to evaluate the ethics of non-disclosure in financial transactions. (Yes, I know you are yawning already) Morality means adhering to what is natural and since lying is unnatural it is immoral. Therefore, using deception to gain an advantage in a sale is unnatural and fundamentally against morality. Even though, as an honest type of a person, I am inclined to agree with this concept, it still seems like a flawed argument and a reductio ad absurdum as well. Cicero spends very little time examining nuance in his argument nor does he address the ambiguous concepts of “natural” or “advantageous” in sufficient detail.

The equation of nature with morality is a problematic construct since morality is inherently subjective and humanistically determined, hence not natural. Deceptiveness is also not unnatural since an insect may have evolved to look like a plant in order to camouflage itself from predators. This would be entirely natural and since being deceptive in this way would further ensure the survival of that individual insect and benefit its species if it successfully reproduces then this deception is not immoral from a human standpoint either. So Cicero’s argument collapses almost immediately and without much effort from the reader. Forging German passports and visas to help Jewish people escape concentration camps would just as well be a form of deception that is morally justifiable. I could imagine Richard Dawkins beating the crap out of Cicero but to be fair I do see the rudiments of game theory in this essay since Cicero argues that more people in society benefit when business is conducted honestly and with minimal conflict than otherwise. Cicero just doesn’t take his argument far enough. His concepts of “moral”, “honest”, “deception”, and “advantage” are not sufficiently defined here, unfortunately, to make the argument work.

The final essay, “On Old Age” addresses the topic you would expect it to. The Stoic Cicero comes out in favor of the elderly, essentially arguing that old age is superior to youth. Since physical strength declines as we age, we get more time to spend enhancing the life of the mind. As a philosopher and ethicist, Cicero is far more concerned with philosophical and educational matters than he is with strength which is good for little more than menial labor and warfare. In his view, the thinkers get to rule society while everybody else gets stuck doing their shitwork. These ideas are neither surprising nor lofty but they are refreshing in today’s world where being young and stupid is valued over being old and wise. It is even worse now with the younger generations that rail against racism, sexism, and homophobia while expressing a vile and nasty hatred towards anybody over the age of forty. Ageism is just as much a form of discrimination as those other ills and expressing ageist ideas can very well be considered hate speech in some circumstances. But in the internet matrix world, young people know everything and old people know nothing so that is just how it is nowadays, be it sensible or not.

Overall, Cicero comes off to me as a morally upright prig, the kind of po-faced killjoy who screams at people for farting in his presence. If there is one thing that John Milton proves it is that we need villains in order to make life interesting. It was the upright and uptight American Puritans who banned Christmas celebrations and alcohol during Prohibition. It is the Islamic Wahhabis and Salafis that try to purify the world by draining all the joy and color out of everything. It is the homicidal monk in Umberto Eco’s The Name Of the Rose who kills someone for laughing, claiming that laughter is immoral because Jesus never laughed. Bone-dry morality is just as boring as a pile of cardboard. Even conman Christian preachers have figured out that nothing puts a congregation to sleep faster than a sermon on righteousness. That’s why the grifter evangelicals have injected so much showmanship into their prosperity gospel with razzle-dazzle stories about going to war against Satan. Why do you think that Qanon inspires fanaticism when Methodism and Lutheranism don’t? While most intelligent people who aren’t sociopaths would be inclined to agree with what Cicero had to say about ethics, that doesn’t mean his beliefs were exciting to read. The people he attacks are far more exciting. He certainly was an important historical figure and I have no interest or intention of taking that away from him, but these Selected Works are little more than a cure for insomnia to me.

Cicero. Selected Works, translated by Michael Grant. Penguin Books, New York: 1971,

Saturday, December 18, 2021

Book Review

You could make the case that the transgressive photographer Diane Arbus sufficiently represented the zeitgeist of the times she lived in. Patricia Bosworth’s Diane Arbus: A Biography, although being unauthorized, has become the standard book for documenting her productive but troubled life. Bosworth does not explicitly claim that Arbus was an avatar representing the values of her times but it is easy to see how this could be true and understanding the values of the 1950’s and 1960s will go a long way in helping you understand the significance of her photos.

According to Patricia Bosworth, Diane Arbus was a precocious child, seemingly almost tailor-made to be an artist. She was an avid reader, felt emotions strongly, and was strangely sensitive to physical sensations, feeling life in every material item she touched. She experienced the world around her at at a much deeper level than everyone around her which, darkly, sometimes led to periods of melancholia and depression. She came from a family of secular Jews with ancestral roots in Ukraine. Her father owned a chain of expensive fur coat stores with their flagship location being on 5th Avenue in Manhattan. Diane Arbus grew up in a sheltered environment with her family protecting her from the negativity of the Great Depression and World War II in their New York City apartment.

In the 1950s, Diane married Allan Arbus, the first boy she fell in love with during high school. Despite their almost inseparable attachment, she simultaneously had romantic notions for Allan’s close friend Alex Eliot, who she eventually had an affair with. The husband and wife team rose to prominence in the art world as fashion photographers, working freelance for Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and Life. They churned out magazine spreads at a dizzying pace like a highly productive factory while maintaining high standards of quality. Their work was monotonous but stable and dependable; still an unease and creeping feeling of dissatisfaction was underlying their lives. If Diane Arbus could be said to exemplify the cultural attitude of the 1950s it would be in this dullness and restraint of emotions. Everything in her life was fine and that was entirely the problem.

Up to this point, Bosworth’s biography suffers from one major flaw. There is very little said about Diane Arbus herself. The author goes into a lot of detail about the people in Arbus’s life but doesn’t say enough about her. There is a lot of information about her family and friends while Arbus just fades into the background. Her absence weighs heavy on the narrative while Bosworth goes into yet another sidetrack discussion about her brother, her friends, or other members of the professional photography community of that time. The author might have been trying to camouflage Diane Arbus in the people surrounding her to make a point of how inconspicuous she could be, but if that was done intentionally, it was taken too far, so far that it interferes with the flow and meaning of the text.

During the ‘60s, Arbus’s life began to change and this is where this biography becomes more interesting. As a fashion photographer, she got used to seeing different sides of her models. Many of them were poor, suffering from depression, or having problems with drugs and alcohol. Some of them were homeless or victims of domestic violence. But when the Arbuses photographed them, they took on a whole other appearance. These displays they put on for for the camera were superficial and fake. She took interest in who these models were in reality. She decided to use her photographer’s talents to explore this other side of life. Diane Arbus began taking pictures of carnival sideshow freaks, homosexuals, eccentrics, the mentally ill, nudists and all other manner of people who existed at the margins of society. She became fascinated with the seedy street-life of 42nd Street. She photographically documented the world of outsiders in America. She didn’t just take their pictures, though. In most cases she spent hours talking to them, getting to know them, sometimes visiting them in their homes, sometimes having sex with them. By getting to know them first, she felt like she could break through to the real people they were. When most people are confronted with a camera, they act as if they want to project to the world how they want to be seen but Diane Arbus wanted to show the world how they really were. By photographing these outsiders, Arbus tried to see something of herself in them, to identify with them and to force the viewer to do the same by confronting us with their images. Her style of portraiture was aggressive, rough, sometimes even intimidating.

For Diane Arbus, this photography was a means of transgressing her own boundaries. She was breaking taboos with her art and likewise in her own life the initial feeling of liberation led more and more to extremes. She became continuously more promiscuous, attending orgies, and going as far as having casual sex with complete strangers in public places. As the 1960s progressed, becoming more and more liberated and free spirited, her life became more disorganized, her marriage ended, and her photography become more popular. But as gallery managers and art dealers hailed her as a visionary and genius, she sunk deeper into poverty and mental illness. Just as the hippie generation ended with the Manson Family murders and the deadly chaos at Altamont, Diane Arbus sank into a hopeless state of depression and committed suicide. It was as if she personally embodied, step by step, year by year, the whole process of lifestyle experimentation, social change, and the undoing of repressions that characterized the counter cultral movement of that pivotal decade. Going so far off the rails and into wildly uncharted territory, unfortunately, led to the simultaneous downfall of both Diane Arbus and the hippies’ strive for utopia at exactly the same time.

In terms of the narrative, Bosworth does a much better job of telling the story in the chapters dealing with the 1960s. Maybe that is because that decade was the most productive and most interesting period of Diane Arbus’s life, but also the author does a better job of keeping unnecessarily extraneous information from intruding. There is still some sidetracking, she provides a lot of biographical information about Weegee even though Arbus did not actually know him, but this sidetracking is less prevalent and the narrative moves along more smoothly as a result.

Diane Arbus: A Biography certainly has its flaws. The writing is sometimes choppy and Patricia Bosworth provides quotes from a wide array of people who don’t seem to be particularly important or insightful for the purposes of this book. These shortcomings are not big enough to ruin it. Patricia Bosworth did a sufficient amount of research to make it work in the end and she succeeds in putting Arbus’s life and oeuvre into context in terms of art history, photography, theory, criticism, and the socio-cultural climate. A definite picture of Diane Arbus stands firm at the end. She was a woman who moved faster than everybody else, so fast that her contemporaries could not keep up with where she was going until it was too late. She reflected and influenced the times she lived in and it is only with hindsight that people are able to see what that means.

Bosworth, Patricia. Diane Arbus: A Biography. W.W. Norton & Company, New York/London: 2005.

Saturday, December 11, 2021

Book Review

Deciding how to evaluate and interpret The Satyricon by Peronius can be a challenge. The main reason is that the text we have is fragmentary, most of it being lost, damaged, or destroyed. Scholars are not even sure if Petronius, a member of Emperor Nero’s court, was truly the author or not. Maybe that does not even matter because almost nothing is actually known about him. Experts in antiquarian literature regard it as satire, but if that is so, what does it actually say about Roman society? With such an incomplete text, the best we can do is draw some meager conclusions based on what little we have.

Although written in Rome, most of The Satyricon takes place on the Greek peninsula of Peloponnesus. The narrative follows the wanderings of a criminal named Eumolpus and his younger boyfriend Giton. At first they are accompanied by another man Ascyltus, but Eumolpus fights with him constantly for the attentions of Giton and they eventually leave him behind. Soon after they meet up with an older poet named Encolpius who latches on to them because he has eyes for Giton too. His poetry is not well received by anybody and his public recitations result in jeering and stone throwing from the audiences.

Like a picaresque novel, The Satyricon is really about the characters and the situations they find themselves in as opposed to an overarching plot. There is no purpose other than to show different facets of Greek and Roman society. The situations begin with the three characters getting abducted by a priestess of Priapus for an orgy that promises to cover the type of literary territory explored by the Marquis de Sade in a later century; as an audience we are criminally deprived of all the raunchy details because those parts of the text are lost. You might wonder if some puritanical Christian in Rome destroyed them on purpose. Eumolpus and friends attend a lavish banquet at the villa of a rich man named Trimalchio where the decadent setting is used as a backdrop for a discussion over whether Rome is suffering from a moral decline or not. That theme is later taken up again when Eumolpus and Giton meet up with Encolpius for the first time. Later, they travel to Italy and stop in the morally corrupted village of Croton. Somehow, Eumoplus gets sidetracked and seduced by a beautiful and nubile woman of a higher class but he is unable to perform; he launches into the longest, and most hilarious, lament about a man facing a male’s biggest fear ever committed to literature.

One great, and complete, story in this book is about a widow who is mourning in her husband’s mausoleum. A soldier is stationed nearby, guarding three criminals being punished by crucifixion. After spending three days making love to the widow, he emerges to find one of the men is missing from his cross. His solution to this dilemma is one of the funniest conclusions in the narrative. It is hard to tell if this was written to be a mockery of the Christian myth regarding the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. It might be coincidental that the details align so well to give an alternate take on that tale but The Satyricon was written in approximately 100 AD and the author was certainly irreverent enough to pull such a satire off. We shouldn’t put it past him to do so.

Overall, there is not enough of the text here to really come up with any grand interpretations of what Petronius intended this work to say. The theme of moral decline is brought up more than once but the earthy humor overrides any moral statement that might have been intended. The story of Eumolpus’s inability to raise wood gets more attention than any prolonged examinations of ethics. In terms of literary history, its style and tone predates classics like The Canterbury Tales, The Decameron, Voltaire’s Candide, and the aforementioned picaresque genre of the novel. The best way to read and interpret The Satyricon is to take it all at face value and leave it at that. Like the Venus de Milo, the ancient Greek statue Nike, or the ruins at Ephesus, despite the missing pieces, you can admire and appreciate whatever is still there.

Petronius. The Satyricon, translated by William Arrowsmith. Mentor Classics/The New American Library, New York: 1960.

Wednesday, December 1, 2021

Book Review

Good quality books on the history of the Civil Rights Movement in America are surprisingly hard to come by, especially considering how pivotal this political movement truly was. Taylor Branch’s Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1953-64 is as good as it gets.

Branch’s first volume in this massive three book series has the great Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as the central figure of the narrative. It all begins with King as a mediocre high school student from a middle-class African-American background who wishes to follow in his father’s footsteps and join the clergy. Extensive details are given about his college education, time spent at divinity school, and the growth of his personal philosophy. While you can see King’s intellectualism start to soar above and beyond that of his peers, these early chapters really do dwell on the subject more than they should have. If you think theological seminaries are not too exciting to read about, this part of the narrative might drag quite a bit.

But the pace revs up and takes off when Martin Luther King begins preaching in Birmingham, Alabama, becomes more acquainted with Gandhi’s practice on nonviolent protest, and embraces racial integration as the purpose of his life. We can see how the bus boycotts, lunch counter sit-ins, picket lines, voluntary jail sentences, and public criticism of the Deep South’s Jim Crow laws propelled him to become the premier leader of this most important socio-political uprising. We also get to see how ugly and evil the southern segregationists really were as they beat, bomb, lynch, and murder any African-American they can find who tries to improve the lives of Black Americans. Taylor Branch does an excellent job of showing just how rotten the people in the South were at that time and just how tyrannical the state governments and police were as they colluded with the White Citizens Council and the Ku Klux Klan to commit acts of terrorism against the citizens of Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi who merely wanted little more than a fair chance at life. Some passages of this book are infuriating to read but honest American citizens need to know all the details of this shameful part of our past so we can prevent our nation from ever sinking this low again.

Along with the activism of Dr. King, we also learn about other organizations like the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, CORE , and the more radical SNCC who later went on to work more closely with the New Left political movements of the later 1960s. These organizations contributed a lot to the Civil Rights Movement by organizing voter registration drives and the Freedom Rides throughout the Deep South after the government banned segregation at the federal level. Branch shows, however, that not all African-American advocacy groups were sympathetic to King and his cause. Surprisingly, the NAACP saw him as a dangerous rival and gave minimal support to his ideas. The African-American Southern Baptist Conference also put up strong resistance to King and his own organization, the SCLC.

Branch’s account of these times are so successful because he provides a street-level picture of how nonviolent demonstrations worked and why it was such a game-changer in the history of American politics. On one hand, the demonstrators were well-dressed African-American groups, sometimes mixed with courageous white supporters, who often made their point by sitting, laying down, praying, and singing church hymns. On the other hand were violent rednecks and police, attacking them with clubs, dogs, and fire hoses, sometimes resorting to using guns and bombs to murder people or blow up their homes and churches. Ultimately, the optics of this all did more violence to the barbaric segregationists than it did to the peaceful demonstrators who looked, more and more, like innocent victims. Rather idiotically, the Southern white people kept claiming that African-Americans were a threat to society and racial integration was inherently dangerous but it was these same white troglodytes who were committing all the acts of terrorism and violent repression. When the media broadcast images of segregationist brutality across the nation, public opinion quickly pivoted to the side of the Civil Rights activists. Branch does a sufficient job of showing the reader what this all looked like. He really puts you in the center of all the action.

At another level of society, President John F. Kennedy and his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, took notice of what was happening in the South which was a Democratic stronghold in their day. Both of the Kennedy brothers felt personal sympathy for the Civil Rights cause but politically it was a dilemma. They didn’t want to turn their backs on their Deep South constituencies but they also wanted to maintain law and order. Martin Luther King had direct contact with Robert Kennedy, but the acting AG dithered while trying to encourage Southern politicians to reach solutions on their own. There were times when the Kennedy brothers were preparing to send federal troops into the South to prevent the police from killing Black people. They had to do this several times in order to enforce the desegregation of public schools. Branch’s portrayal of the Kennedys may leave the reader with mixed feelings about them. They checked their personal feelings to uphold the law even though the law disgusted them. This had the effect of trivializing the Civil Rights cause in the eyes of its adherents. It was all a tricky situation for John F. Kennedy because he won the presidential election with support from both the segregationists and the desegregationists. It is easy for us to criticize the decisions a president makes but considering that most of us never have been, and never will be, in that position of power we might not be the best ones to make those kinds of judgments.

Another political layer to this history is that of J. Edgar Hoover the sinister activities of the FBI. Hoover was an outright racist who hated African-American people. He especially had a personal hatred for both Martin Luther King and John F. Kennedy so he set the FBI on a task to destroy them and the organizations involved with the Civil Rights Movement. He was convinced that Dr. King’s SCLC was infiltrated by communist agents with direct ties to the KGB. The FBI did extensive wiretapping and espionage operations on King and his associates. When they failed to turn up evidence, Hoover fabricated it, claiming that Dr. King’s lawyer and closest white friend Stanley Levison was being paid by the Soviet Union to destabilize America. Branch shows us how sick-minded J. Edgar Hoover really was. In light of the spying they did, and probably still do, on American citizens, you might question whether America is really all that different from any other totalitarian nation or not. Just remember that the US government was against racial integration until it became a viable issue for strategically winning elections.

Other fascinating topics covered in this book are the Ole Miss Riots that happened when James Meredith tried to register as the first Black student at the University of Mississippi, the assassination of the NAACP leader Medgar Evers, Dr. King’s writing of the landmark essay “Letter From a Birmingham Jail” in which he castigated the hypocrisy of white segregationist clergymen, and the 1963 March on Washington where Martin Luther King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech.

The biggest problem with this book is its size. At over 900 pages, there are a few parts that could have been edited out. While the majority of Dr. King’s work was not direct political action, it was actually organizing, planning, and fundraising, the details of every meeting he ever attended are not necessarily important. The same can be said for White House cabinet meetings. Some of the information also gets redundant, especially Branch’s mentioning of John F. Kennedy’s extramarital affairs. For example, the tryst that Kennedy had with a possible East German spy may be relevant to the discussion about his contentious relationship with J. Edgar Hoover and why he insisted that King throw Stanley Levison under the bus to placate the FBI director, but Branch goes over the details too much so that it just seems like a waste of paper after a couple paragraphs. Then there are other important parts that do not get sufficient detail. Little is said about the Constitutional Amendment and federal legislation passed under the Eisenhower administration and the emergence of the Nation of Islam along with Malcolm X are mentioned only briefly.

Taylor Branch’s Parting Of the Waters, despite its length, is an easy book to get engaged with. The subject matter is important and it can really change the way you look at American society and race relations. Even when the author preachers to those of us who already members of the choir, it is still an eye-opening narrative. The next time somebody asks about the ten books you need to read before you die, this should certainly be one of them.

Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America In the King Years 1954-63. Touchstone Books/Simon and Schuster Inc., New York/London/Toronto/Sydney/Tokyo: 1989.

Monday, November 29, 2021

Inside the Infamous NYC Riot That Got Six Cops Indicted

Friday, November 26, 2021

Spend a night in 'hell': The last days of the Hotel Cadillac

Thursday, November 25, 2021

The 1962 University of Mississippi Riots That Changed The World

Wednesday, November 24, 2021

Understanding Tommy Wiseau's Net Worth: How and Where Did He Get His Money?

Friday, November 19, 2021

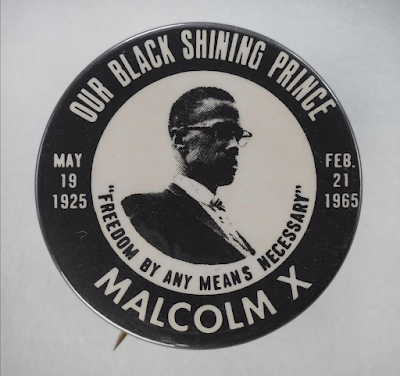

Two Men Wrongfully Convicted of Killing Malcolm X Are Exonerated After 55 Years

Thursday, November 18, 2021

Mommy Dead and Dearest

Sunday, November 14, 2021

Barry Goldwater's Presidential Campaign of 1964: The Politics Of the Lowest Common Denominator

Barry Goldwater was not a man of his times. Nor was he a man of later times, earlier times, or our present times. He was a man of no times, maybe even a man of all times. To say that he lost the American presidential election of 1964 by the biggest landslide in history because he couldn’t connect with the voters is an understatement. In more recent times, and despite this crushing defeat, political pundits have hailed Goldwater’s campaign as the beginning of the late 20th century American Conservative movement. But a careful examination of Goldwater’s values proves that back in the 1960’s, and all throughout his life, he did not share many of the core beliefs that characterize what we call today the conservative right wing. There simply must be something besides beliefs that has brought political historians to that conclusion.

Barry Goldwater was born in Phoenix, Arizona in 1909 to the son of an immigrant Polish Jew. His father owned an upscale department store called Goldwater’s and married a wealthy woman named Hattie. In order to further assimilate to American culture, the family, including Barry Jr. and his two brothers, were raised as Episcopalians. Barry, however, had little regard for religion and spent his life considering himself a secularist more than anything. In high school, Barry Goldwater was a mediocre student with a steady C average. He excelled in sports, though, and after graduation he went on to college but dropped out due to lack of interest in academic subjects. Not only did he go on to be the first and only presidential candidate to be of Jewish ancestry, he was also the only one to have never attained a college degree. His lack of intellectual prowess did not hold him back in life, though; during World War II he enlisted in the air force and got decorated as a war hero after the allied victory.

Goldwater’s political career began in 1949 when he got elected as a member to the City Counsel as part of a nonpartisan team dedicated to the eradication of gambling and prostitution in Phoenix. As a Republican, he also helped to rebuild the moribund local party apparatus. Later, he successfully ran for senator of Arizona. His election came as a surprise since his home state was a Democratic stronghold at the time. Barry Goldwater was deeply committed to desegregation and the Civil Rights Movement; he helped to set up the first NAACP chapter in Arizona and showed strong support for the Urban League.

During the 1950s, he also gave support to Joseph McCarthy and his witch hunt against Communists in American society. Goldwater’s fervid anti-Communist stance would be a hallmark of his belief system throughout his life. The fact that this stance contradicted his support for the socialist-leaning Urban League did not appear to cause any moral conflicts in his mind. Goldwater’s outspoken dislike of the New Deal Coalition established by Franklin D. Roosevelt also gained him notoriety in the Senate, especially because he criticized President Eisenhower’s economic policy as being a cheap knock-off of the New Deal. Goldwater also attacked what he called the liberal wing of the Republican party, thereby making enemies of future presidential candidates like Richard Nixon and Nelson Rockefeller who he deemed to be too far to the left to be truly American. Despite his distaste for the liberal brand of politics, he was a close personal friend of John F. Kennedy. When Goldwater told Kennedy that was planning on running against him in the 1964 presidential election, the two agreed to avoid any negative campaigning, running as two friendly rivals since they both disliked the idea of turning the American voters against one another along partisan lines.

Barry Goldwater was conservative in the sense that he valued individual freedom over the collective good. He didn’t like big government or welfare and he certainly didn’t like Communism. Such ideas are run-of-the-mill conservative strawman tropes. But Goldwater was unable to see how these beliefs smashed into a wall of obvious contradictions in light of his other beliefs. For example, the Civil Rights Movement was very much about support for the common good over the rights of the individual. Enforcing desegregation laws also requires big government interference in the lives of individuals; without a mandate at the federal level, it would be impossible to enforce integration. His ideas on crime and foreign policy also deconstruct themselves with minimal effort under examination. Goldwater claimed a strong police force with sweeping powers was necessary but this idea of a police state contradicts the idea of big government intervention. It also fails to account for how the police force and the FBI were instrumentalized by the government to oppress the African-American people he claimed to support.

Foreign policy was not one of his strong points either since he claimed to be in favor of minimal foreign intervention in conflicts overseas while being hawkish, pro-war, and supportive of military expansion. Goldwater failed to recognize that overseas wars might not effect individual freedoms on American soil but they do effect the individual freedoms of people living in foreign countries, especially when the US government interferes with elections, overthrows governments they don’t like, and installs dictators to act as puppets for the American empire. Holding the double standard that individual freedom is good for us while oppressing nations leads to a cockeyed morality and a distorted view of the world. Were Goldwater’s beliefs an intellectual sleight of mind trick meant to distract us from reality? No. Barry Goldwater, the college dropout, was a classic example of the American anti-intellectual, so deficient in critical thinking skills that he could not see his own contradictions parading themselves across his line of vision. Otherwise, though, he was a very nice man with a pleasant personality. For certain types of Americans, that is more important.

Such was the kind of baggage Goldwater would bring into the presidential election cycle of 1964. Just as the Republican Party candidates were gearing up for the primaries, a couple major events took place. One was that President John F. Kennedy, the expected candidate for the Democratic Party was assassinated in Dallas by Lee Harvey Oswald. The other was that Lyndon B. Johnson, the new sitting President, ratified the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Before the assassination, American paranoia about nuclear war and Communist infiltration was already high. The Bay of Pigs and the Cuban Missile Crisis had recently happened while the Berlin Wall was under construction. Government discussions involved plans for building fallout shelters in case of a nuclear attack. But the assassination of Kennedy took public discomfort to a whole new level as paranoid conspiracy theories began to circulate. Despite this dark shadow cast by the Red Menace, the Civil Rights Movement was the issue of the day. Jim Crow laws had been taken off the books, Freedom Riders had been beaten nearly to death by barbaric Southerners in Alabama, Malcolm X had been assassinated, and Martin Luther King Jr. was leading a non-violent movement towards racial integration, the likes of which no nation on Earth had ever seen before. As a Senator, Barry Goldwater had voted to ratify the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and the 24th Amendment to the Constitution, but in 1964, he voted against Johnson’s new Civil Rights Act. It wasn’t that Goldwater was against Civil Rights. His past involvement in the cause was nothing short of commendable. He just took issue with the bill giving the federal government more power than he thought it deserved. He was, after all, an advocate of states’ rights over federal rule. This emphasis on states’ rights sounded too much like neo-confederate ideology for the times he was living in. States’ Rights was the battle cry of the Confederacy before the Civil War began, unfortunately for the tin-eared Goldwater. These poorly thought out positions would come back to bite him later in the campaign when African-Americans showed in droves to support Johnson.

During the Republican Party presidential primaries, Nelson Rockefeller of New York started off with a strong lead. His popularity declined sharply when he announced his engagement to a woman younger than him by eighteen years. The prudent conservative base rejected him even more when it was revealed that she had recently gotten divorced and was soon in labor, giving birth to a child obviously conceived out of wedlock. Rockefeller’s momentum died out and he sank by twenty points in the polls. In the initial primary vote, Henry Cabot Lodge emerged as the front runner even though he was not officially on the ballot; he was, in fact, a write in candidate.

But Barry Goldwater continued to campaign with his message being that the Democrats and the Republicans had too many similarities. He denounced the liberal wing of the Republican party as a group of East Coast, overly-educated elites who were out of touch with the common people. He wanted to take the party further to the right and went so far as to say the entire Eastern seaboard should be cut off and separated from the rest of America. Needless to say, calling for an entire section of the country to be forced into secession, the part of the country with the highest population density and the biggest number of voters, was not a wise election strategy. Goldwater did, however, emerge as the front runner.

At the 1964 Republican National Convention, shouting matches broke out between the liberal and conservative wings of the GOP and Nelson Rockefeller got booed while making a speech. The liberals roundly denounced Goldwater but he pulled ahead in the ballots and became the clear nominee, choosing William E. Miller of New York, one of those East Coast elites, as his vice-presidential running mate.

As the election cycle of 1964 started, Lyndon B. Johnson, running with Hubert Humphries for vice-president, was riding a wave of popularity. In part this resulted from serving a term in office as vice-president under the wildly popular John F. Kennedy whose stature grew to even more enormous proportions after the assassination. Another factor of his support resulted from his recent ratification of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, although this created another problem for Johnson: he lost major amounts of sympathy from the electorate of the Deep South, previously considered a Democratic stronghold because of Roosevelt’s New Deal which lifted large portions of that population out of poverty. Another setback for Johnson was his escalation of the Vietnam War which was starting to look questionable in the eyes of a small but vocal part of the young American community. On the other hand, Johnson campaigned on the implementation of his pet projects called The Great Society and The War on Poverty which proved to be visionary in scope and were supported by an overwhelming segment of America. Democrats always do their best when they aim high.

On the contrary, Barry Goldwater had little to run on. In an age of nuclear terror, he promised to dramatically escalate the arms race, believing that an increase in the size of America’s arsenal would guarantee victory if a war were to break out. He proposed funding for the development of nuclear grade tactical weapons, like military assault rifles and hand grenades, to be carried by ordinary soldiers on the battlefield. He proposed doing away with the military bureaucracy that prevented commanding officers from issuing such weapons to foot soldiers on the ground He also proposed using executive orders to bypass Congress, enabling the President to declare war unilaterally. This small government ideologue advocated for a form of legislative overreach without realizing that Congressional approval serves the purpose of preventing any branch of government from becoming too powerful. Goldwater the Conservative argued against a conservative system of checks and balances that is necessary to prevent executive tyranny. He also proposed launching nuclear attacks against North Vietnam and the Kremlin in Moscow. At a time when people were preoccupied with preventing nuclear war, Goldwater was saying he wanted to start one.

Such thinking made Goldwater an easy target for attacks from Lyndon Johnson who accused him of being a right-wing extremist, getting most of his support from kooks and political cults like the conspiracy theory-mongering John Birch Society and the Ku Klux Klan. Support for Goldwater from the latter organization was especially curious considering Goldwater was an ethnic Jew and an advocate of desegregation but his misguided opposition to Johnson’s Civil Rights Act, and the hatred they had for the incumbent president, made them strongly support Goldwater nonetheless. Another one of Johnson’s attacks was even more harsh. He produced a television campaign ad that has come to be known as Daisy Girl. The commercial was shown only once before it got pulled off the airwaves by the networks. It showed a young girl picking petals off a daisy while counting to ten. Then a man off screen counted down from ten to one; this was followed by a nuclear explosion with two mushroom clouds. Lyndon Johnson’s voice-over explains that we need to create a world based on love where all people are safe to live. The final segment has a deep-voiced man saying “Vote for Lyndon Johnson on November 3, the stakes are too high.” The clear implication was that a Goldwater presidency would result in a nuclear holocaust.

More negative publicity came Goldwater’s way when Fact magazine published an article about the Republican contender’s mental health. It explain in detail how the make-up of his psyche was too fragile for him to handle the office of the presidency. It ended with a petition signed by more than 1000 psychiatrists who claimed that Barry Goldwater was psychologically unfit for political office. Goldwater’s performance during debates, interviews, and Q and A sessions did not lend him any credibility. His speaking was evasive, characterized by empty sloganeering and circular logic that made him appear as if he didn’t know what he was talking about. His belief that the government was secretly hiding UFOs further cemented his image as a flaky nutcase. Lyndon Johnson, while not especially attractive, was an eloquent and highly-skilled speaker who could talk circles around Goldwater without much effort.

Worse than all this was the fact that Barry Goldwater could never extend his popularity beyond his own miniscule base of conservative Republicans. Liberal and moderate Republicans all flocked to the Democratic side in support of Johnson. Goldwater’s narrow messaging never connected with anybody in the opposing political party and it certainly drove independents farther to the left.

Goldwater did attract the attention of a politician whose star was rising and would prove to be more influential in the future. Ronald Reagan at that time was a barely known actor, making corny unwatchable B-movies like Bedtime for Bonzo in which he fed a chimpanzee. His wife too was a complete airhead named Nancy whose biggest role was in a science-fiction film called Donovan’s Brain. Somehow it slid by the censors during the McCarthy era when leftist themes were less tolerated. Ironically the film was about a corrupt, power-hungry businessman who gets brought back to life. While the film is not explicitly pro-Communist, it certainly does have an anti-capitalist message to it. Reagan’s greatest political asset at that time was that he was the President of the Actor’s Guild, another irony since Goldwater was against labor unions. He saw his opportunity to transition from Hollywood to Sacramento to Washington, D.C. and jumped on Goldwater’s tiny, shrinking bandwagon. The future President made one campaign speech praising Goldwater’s shallow ideology. Two years later, Ronald Reagan would get elected governor of California and then go on to be elected President in 1980, defeating Jimmy Carter.

Come election day, Lyndon Johnson slaughtered Barry Goldwater in the polls. He broke voting records on two counts. With 486 electoral votes to Goldwater’s 52, Johnson took the highest number of electoral college votes in history, a record only to be surpassed by Ronald Reagan in 1980. Johnson also received 61% of the popular vote, a number that has never been surpassed by any candidate yet. President Lyndon Johnson defeated Barry Goldwater with the biggest landslide victory in the history of American elections. The only states taken by Barry Goldwater in the electoral college were his home state of Arizona, which he barely won, and the Deep South states of Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and South Carolina. These Dixiecrat states went red largely in opposition to the Civil Rights Movement. Once again, the Confederacy was on the wrong side of history. It probably won’t be the last time either.

The election of 1964 represented a major turning point in American politics. Not only did it launch the governmental career of Ronald Reagan but it also turned the once Democratic South towards the conservative Republican Party. It also marked a shift in the voting preferences of African-American people who were traditionally supporters of Abraham Lincoln’s Republicans and have been predominantly supporters of the more inclusive Democratic Party ever since.

Although Barry Goldwater lost miserably, political scientists see his campaign as the start of the modern Conservative movement in America. In some ways he is an odd choice for such a dubious honor. The conservative public intellectual William F. Buckley Jr., after the bloodletting campaign of 1964 ended, commented that Goldwater made Conservatives look like a bunch of simpletons. In any case, he unwittingly hit on a painful truth. Most likely it was not what Barry Goldwater believed in or said that made him the forefather of Reagan-era right-wing politics, it was his approach that did it. Goldwater, the college dropout and anti-intellectual, once said that the American people were not complicated and appreciated simplicity more than anything. Goldwater, the clean-cut, pleasant sounding man fit this role perfectly. He communicated his message with ease, without parsing over and fine details or potential flaws. He appealed to those who work hard and think little, the low-information voters. He dragged political debate down to the lowest common denominator, a tactic that Fox News, with their bullying and infantile temper tantrums, have been running with for the last twenty years.

The historian and political sociologist Richard Hofstadter may have been the first to draw a connection between Barry Goldwater and the kind of people he inspired. In his landmark book of essays called The Paranoid Style in American Politics, he connected Goldwater to a certain class of conservative Americans. These are white, middle class people with low levels of education. They are suspicious of government while being loudmouthed about their patriotism and loyalty to their country. They know little about policy or economics, dislike foreign intervention but strongly support any war America wages. They believe in individual freedom but despise anyone, be they freaks, hippies, pacifists, homosexuals, or punks, who expresses their individual liberty in ways that are different from their own. Prone to conspiracy theories, they often think the establishment has fallen from grace, being infiltrated by foreign agents like Communists, Jews, Catholics, the Illuminati, Freemasons, immigrants, and the United Nations. Millenarian in their thinking, they believe society is on the verge of collapse at all times. These thought patterns are common among the Calvinist and Evangelical Christian belief systems, with deep roots in the Puritan sect that arrived in America so many years ago. These are the people who Ronald Reagan rallied in the 1980s and have since degenerated into a mean-spirited form of hatred, narrow-mindedness, and nationalism inspired by the likes of Newt Gingrich and Rush Limbaugh, culminating in the dystopian rise of reactionary ignoramuses like Sarah Palin and the quasi-fascism of Donald Trump. These are the people who became post-Goldwater Conservatives.

Such a legacy may not be entirely fair to Barry Goldwater. If he were alive today, he would be horrified by what the Republican Party has become. During the 1970s he took a break from politics and re-emerged once again as a Senator. While he expressed some admiration for Reagan, he was not entirely happy with what Conservatism was. He was critical of Reagan’s interventions in Central America and condemned the sale of arms to Iran in order to illegally fund a right-wing dictatorship in Nicaragua in what came to be known as the Iran-Contra Affair. Being an advocate of marijuana legalization, he dislike the disastrous War on Drugs. He also disliked the Religious Right, believing them to be a pseudo-totalitarian form of surrogate big government. Goldwater said that Jerry Falwell deserved to be kicked in the balls and complained that Pat Robertson was little more than a charlatan, a petty conman, and a grifter. He was a staunch advocate of environmental protection and believed heavy taxation on big industries would force them to reduce carbon admissions on their own at the source of production. He advocated for gay and lesbian rights along while being a supporter of gay marriage. He was pro-choice, believing a ban on abortion constituted government interference in a woman’s right to control over her own body. These are an incredibly liberal set of beliefs coming from a guy who is thought of as the godfather of the Conservative movement. In fact, Goldwater was once known to have said that most liberals are actually fine people with outstanding moral standards. All these contradictions go right over the heads of low-information Conservatives with their love of simplicity, lack of curiosity, and anti-intellectualism that prevents them from seeing the obvious.

If Barry Goldwater can represent anything definite in our times, he can act as a symbol of futility, the dysfunctionality of pigeonholing people into categories of belief. As a right wing Conservative, his ideology does not hold up well under scrutiny. As a Liberal, he doesn’t do any better. Realistically, today he would be a blend of Ron Paul and Bernie Sanders, more likely an Independent than a Republican or Democrat. If he hadn’t died, he might exemplify the virtue of maintaining a voice independent of the hostile tribal partisanship that is crippling American politics. But then again, maybe not. His method of polite delivery and shallow reasoning might make him sufficiently non-committal to any party but being in such a central position might only result in his being shot at from all sides at once.

Friday, November 12, 2021

Thursday, November 11, 2021

FW de Klerk: South Africa's former president dies at 85

Monday, November 8, 2021

Princess Emiluma, The Story Of Srebrenica, & Bob The Blob

Sunday, November 7, 2021

Finding Goatse: The Mystery Man Behind the Most Disturbing Internet Meme in History

Wednesday, November 3, 2021

Freedom Ride

Tuesday, November 2, 2021

QAnon supporters gather in downtown Dallas expecting JFK Jr. to reappear

Some believe the reappearance of John F. Kennedy’s son, who died in a plane crash in 1999, will bring about the reinstatement of Donald Trump as president.

Thursday, October 28, 2021

Highlander Folk School

When people think of the civil rights movement, they often think of Selma or Montgomery, Ala., Atlanta or Memphis.

Maybe they should think of Grundy County, Tenn.

After all, it was at the Highlander Folk School in Grundy County that early civil rights strategy was mapped out. At Highlander, white and black activists — including Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks — met in the 1950s to talk about how they might change the South. It was at Highlander that many civil rights leaders trained

Book Review

Brutal. Absolutely brutal. Greek and Roman history were saturated with violence, blood, and gore. People who naively believe that past times, particularly in antiquity, were simpler or more meaningful would benefit from reading Plutarch’s Lives before making such a statement regarding values.

The Greek author Plutarch was primarily a philosopher concerned with the branch of ethics. This epic anthology of essays reads more like historical biography, though. Each chapter tells the life story of a Greek or Roman general or politician, with the Persian Artaxerxes being the sole exception. These biographies are paired in an unaltered succession of Greeks and then Romans in that respective order throughout the whole collection. At the end of each pairing, a short comparison of the two regarding their strengths and weaknesses provides an evaluation to explicate which of the two proved to be more virtuous. As a work of ethical philosophy, Lives does not stand on its own very well. This is mostly because the evaluations are short and sketchy while rarely every coming to any strong conclusions while the biographical histories are bulky and overloaded with detail. The ethical comparisons are the weakest parts of the book,

So be it. Lives may not be a profound ethical treatise but as a source of history it proves to be a rich and rewarding read. At the beginning we are treated to writings about the early days of Athens and Sparta alongside the foundations of Rome. This includes the classic story of the Rape Of the Sabine Women. The first third of the book mostly details battles, wars, and minor military skirmishes with the central theme being about the generals who led these melees. This first part of the book is exciting at first but quickly becomes redundant in its descriptiveness; there are only so many battles that armies can fight on foot and horseback, using swords, shield, and arrows before they all start sounding the same. Aside from classical warfare strategies, many of which resemble plays in modern team sports, scattered bits of interesting trivia do emerge. For instance, it becomes easy to see why the eagle was adapted as a symbol of Roman military superiority since their warriors would line up with a left wing and a right wing to swoop down on their enemies, just like a bird of prey. Plutarch also heaps praise on the head of one Greek general who invented the iron helmet because wearing such a heavy headpiece would cause a combatant’s sword to break when striking the head of their opponent. This sounds like a good idea on the surface but the modern reader has to consider the wisdom of wearing a twenty pound piece of metal on their head in the sweltering Mediterranean climate. Being smacked with a sword while wearing an iron helmet could not have felt pleasant either. This was centuries before aspirin and acetaminophen were invented too. Warfare in those days could not have been much fun and from the looks of it, that was the primary occupation for men in those days.

Further into the book, the historical themes begin to vary. As the Greek and Roman Empires expand outwards, the lifestyles and personalities of their leaders get described in greater detail. The most familiar names like Cicero, Cato the Younger, Alexander, Julius Caesar, and Antony are the literary high points of the Lives. Alexander of Macedon does more than inherit Greece from his father, Philip, who conquered the territory; he also marches across Persia and India, expanding the eastern border of the Greek Empire. Alexander’s conquest of India is curious. There were a few small battles here and there, some diplomacy and negotiations every now and then, but mostly he rode around with a fleet of boats, entering village after village to declare each one his own territory. You just have to wonder how seriously his new subjects took him after he left and never came back again.

One of the great elements of Plutarch’s writings is the way he points out multiple perspectives on individuals and events. Along the way, he mentions conflicting details as written in different source materials, but this element of shifting perspectives is really driven home in the telling and re-telling of the life of Julius Caesar. The story of his turn from senatorial consul to dictator, along with the transition of Rome from a republic to an empire, is examined from the points of view of Pompey, Cicero, Antony, Brutus, and Cato the Younger, among others, each in their respective biographies. Thereby we see how he could have been taken as a hero of the people or as a power-hungry tyrant depending on who you ask. The idea that news is always biased is not a contemporary notion as Plutarch demonstrated this principle here, possibly also keeping the doors open to moral relativism for future generations since the ethics of Caesar’s assassination are ambiguous from the standpoint of those involved in the plot.

Yet another interesting aspect of Plutarch is his chronological overview of the Greek and Roman Empires. This was not his intention in writing the Lives but the historical patterns emerge nonetheless. If you are inclined to think of the two ancient superpowers in terms of stages succeeding one another, you get a different picture from the way the biographies are paired and contrasted. It would be more accurate to say that Greece and Rome ran along parallel paths until the Greeks were absorbed into Macedonia and then began expanding outwards. As they began to decline, Rome ascended and the two merged into one another. Plutarch himself was a product of this historical process being an Athenian who moved to Rome and based his writings on research he did from books kept in that dominant city of the Italian peninsula. By the end of this book, the Greek and Roman armies are so intertwined, it is difficult to tell them apart. An interesting pattern emerges in Rome too. As the Romans expand westwards into Gaul and Spain, then eastwards across Turkey, called Asia in these histories, and further into Parthia, Armenia, and Syria, the city of Rome begins to implode with lots of civil disturbances, assassinations, and violence between factions competing for power. The idea that Rome fell as a result of barbarian invasions does not stand up so strongly when it becomes obvious that localized, civil strife did a lot to weaken the republic from the inside before the Goths or Vandals showed up on the scene long after Plutarch died.

Despite its relevancy to historical narratives, Plutarch’s Lives, with its glut of information, may not always be an easy read for modern audiences. While he attempts to write biographies of each personage, this writing is not biographical in the way we understand it in today’s world. This was written long before psychology was conceived of as a means of interpretation so what we get are examinations of character traits and behaviors, mostly looked at through a lens of moral judgment. While there are a few comments on subjective motivations here and there, hinting at what we would consider an inner life by today’s standards, the people of this book act as if they are pushed and pulled by instincts and impulses while the finer elements of their psychology are projected outwards into the machinations of the gods, some of which are revealed to them by auguries and divination. As we now know, such fortune telling is far from an exact science. It makes for interesting poetics though. The writing is often long-winded too but this could be a fault of the translator’s.

Plutarch’s Lives is a tough and masculine book, permeated with violence from beginning to end. Every pages details warfare on both land and sea, along with governmental overthrows, torture, punishment, assassinations, and suicides. Most of the descriptions are not quite as graphic as what Homer wrote in The Iliad, but Plutarch does have his vivid moments of sadistic fascination. You can easily get the impression that the ancient peoples of the Mediterranean did little more than fight and kill each other, but it would be unwise to overstate that idea since the Greeks and Romans contributed so much to the evolution modern culture, the humanities, engineering, and politics that we should not forget the enormous debt we owe to them for these advancements, made when people had so much less than what we have now. Overall, Plutarch is not for the general or casual reader, nor for the faint of heart, but his Lives are a real treasure for those with an honest curiosity about the ancient world.

Plutarch. Lives, translated by John Dryden. The Modern Library, New York.